written by Dr. Victor Ezquerra, Metro Music Makers instructor

Music accomplishes many things. It has practical utility that can be applied to many endeavors, it can be used to communicate information and emotions, it plays a substantial role in culture, it provides entertainment, it gives people an outlet to be creative, it helps us understand beauty, and it has value on its own.

If you would like more information about our piano lessons in Atlanta, or if you want to explore the violin, learn to sing, or play another instrument contact Metro Music Makers at your earliest convenience.

Introduction

This blog takes a departure from more practical musical issues and applications to focus on a philosophical question: What is the point of music?

While it may seem like a question that is overly simple or possibly unnecessary to explore, it is one that music educators and music lovers frequently find themselves answering. Lack of institutional funding often puts music teachers in the awkward position of having to justify their existence amongst the increasing focus on STEM learning. Music advocates frequently have to give reasons why the arts should be included in the curriculum and are important for all students. In turn, this becomes a worthy question for those who wish to learn music outside of schools because they may be confronted: “Music is just playing around; what else does it accomplish?” or “Why should I be learning about music?” or “Is this worth the time or the money?” The short answers to those questions, respectively, are: a lot, for many reasons, yes and yes.

So why do music? Below I have provided a brief overview of some of the uses, applications, functions, outcomes and purposes of music. This list is by no means exhaustive nor comprehensive. As with most philosophy, the aim is not to provide absolute certitude. The goal of this blog entry is to stimulate interest, evoke critical thinking and spur action.

Quick aside: get more information about our:

- piano lessons in Johns Creek

- piano lessons in Marietta

- piano lessons in Alpharetta

- Sandy Springs piano lessons

Does Music Have Practical Utility?

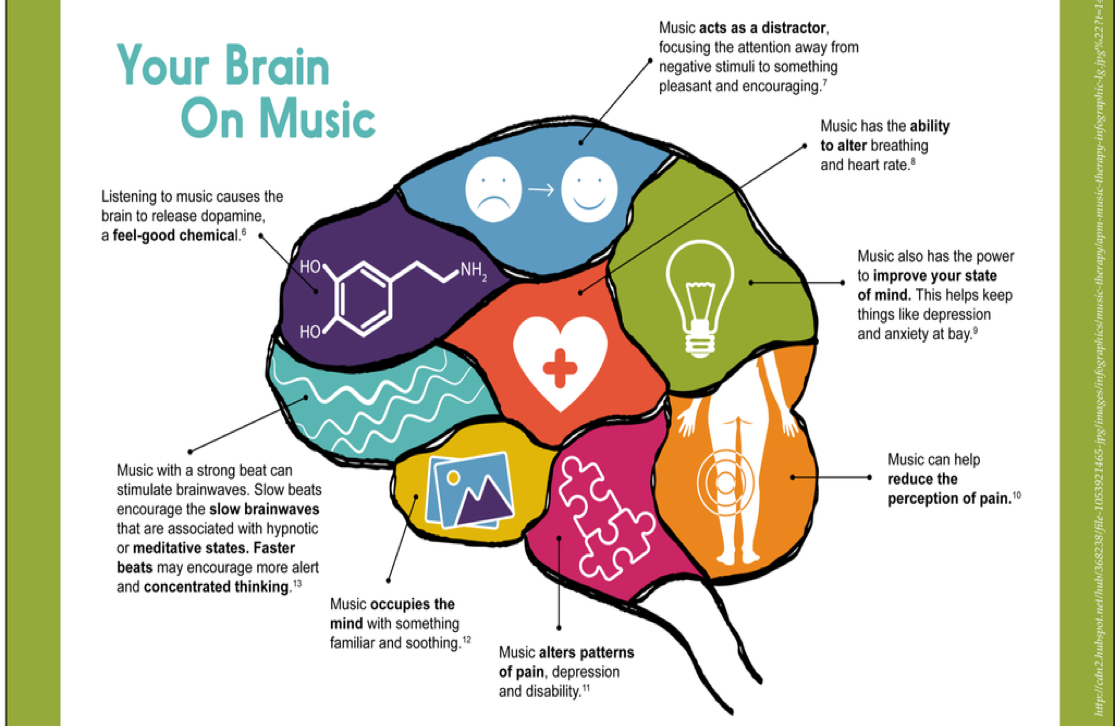

Yes! Music has many practical uses; it is a powerful tool. Many people use music to alter the body’s response to physical tasks. Research has suggested that music can aid people in longevity and intensity of strenuous exercise, promote relaxation, and refine motor skills (Harmon and Kravitz, 2007). Different musical selections can influence retail behavior including satisfaction with a dining experience (North and Hargreaves, 1996) and purchases made (North, Hargreaves, and McKendrick, 1999). In more menacing instances, music has been used as “psychological warfare” to wear people down during standoffs and to torture terrorists.

There is a long history of music having therapeutic applications. Indigenous tribes in North America utilized the healing power of music. In Europe, from antiquity to the renaissance, “If music cured, it was by acting upon the entire human being, by penetrating the body as directly, as efficaciously as it did the soul” (Foucault, 1965). Today, music therapy is a young and rapidly growing clinical field. Research has focused on medical improves speech, mental illness, pain, dementia and numerous other physical ailments.

Religious music and work songs provide two examples of music that exist to accomplish specific ends. Work songs are an amusing distraction from the job, make time go by more quickly, and coordinate group efforts. For slaves working on railroads or chopping trees, work songs broke up the monotony of their tasks, and ensured they synchronously swung axes/hammers at the right time and avoided injury. A lot of religious practices have all the qualities of what we consider to be “music,” but are used solely as spiritual activities. The Islamic azan, a call to prayer that happens five times each day, might sound like someone singing but is intended to notify followers that it is time to pray. In Africa, the Shona tribe uses mbira music to spiritually connect with their ancestors. Although work songs and religious music can be aesthetically pleasing and culturally relevant (see the section below), they have particular functions in real-world contexts. (Titon, 1984)

How Is Music Used to Communicate?

“Music is a powerful means of communication. It provides a means by which people can share emotions, intentions, and meanings even though their spoken languages may be mutually incomprehensible” (MacDonald, 2005).

Transmission and communication are some of the most practical uses for music. On a very basic level, sound is used to represent information. Some sounds communicate obvious messages like a cell phone ring (someone is contacting you), the tones of an ambulance (caution), or the melody of a doorbell or appliance (something requires attention). This is not a new phenomenon, nor is it a rare one. Musical instruments like bugles have been used by armies to give orders from a distance; African tribes used the lunga (talking drum) to send messages between villages.

On a deeper level, music is used to communicate emotions. Expression is a highly recognized function of music. Throughout the history of humankind, music has provided an outlet for the people to express happiness, sadness, pride, anger and basically every other emotion we can feel. Not only can we share our own feelings, but music can also allow us to experience the feelings of others. The connection between music and emotions can be fun and lighthearted, and it can also be profoundly intense. Playing or listening to music provides an outlet for our emotions and an opportunity for communication without words. Writer Hans Christian Anderson noted: “Where words fail, music speaks.”

What Role Does Music Play in Culture?

Not only does music play a significant role in all cultures, we also create specific cultures based around music. Titon (1984) defines music-culture as: “A group’s total involvement with music: ideas, actions, institutions, material objects—everything that has to do with music.” For example, rap culture has its own unique language, gestures, venues, labels, instruments, clothing, rituals, values and beliefs. Music cultures are also dynamic. Rap culture changes with time and location, and can also be divided into sub-cultures like Atlanta rap culture

or conscious rap. These cultures can be as large as a nation, or as small as a single person.

Music is a large part of social identity. It is extremely common for people to be members of numerous music cultures simultaneously, and that shapes who we are as individuals. Some of my own music cultures include my family, who formed my earliest musical tastes, bands I have played with that have their own repertoire (collection of works) and style, my colleagues in music education who influence my beliefs and practices, my race/ethnicity/nationality, which imply certain languages and styles, and my own personal preferences, which impact how, where, why, and when I listen to and play music.

For humans from any and all cultures, music helps define who we are and brings us together. Music has often been called a “universal language” because it allows us to socialize and find commonalities despite all our differences. We can share our own music with others and vice versa. We connect and relate with people on a deep level. When we listen to sounds created by total strangers, we can get to know them, and ourselves, more deeply.

How Is Music Entertaining?

It is clear that music can serve as a valuable means to entertain. Although it may never be known exactly what they were used for, researchers have suggested that one of the oldest musical instruments that dates back 42,000-43,000 years may have been used for recreation. Side note: the human voice is the oldest musical instrument, which is also used for entertainment, but of course there are no fossilized vocal recordings. From prehistory to present day, we love to have fun with music.

There are countless ways to be entertained by music. Just sitting and listening to music is pleasurable, whether it is done alone or with others, or through recorded audio or live performance. Undoubtedly, making music is a lot of fun and can be done in a multitude of ways, which includes singing, performing, recording, editing, producing, arranging, writing, improvising and composing. Music also makes other aspects of life more exhilarating. Singing in the car or shower, listening while cleaning or cooking, and dancing along with a favorite song—these are just a few examples of how life is more fun with music.

Frequently cited and used by music educators, Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) emphasized the importance of play in child development and socialization. Vygotsky discussed the concept of “play,” which can be done with music in any of the ways mentioned in the paragraph above. When we “play” with music, we learn valuable skills for interacting with other humans, improve cognitive function by constructing knowledge, and sharpen problem-solving skills (St. John, 2010). While musical play is exciting and enjoyable, it also has unexpected benefits.

How Is Music Aesthetic?

Another one of music’s primary purposes is aesthetic. After all, music is an art form. Merriam-Webster (2020) defines aesthetic (n.) as: “a branch of philosophy dealing with the nature of beauty, art, and taste and with the creation and appreciation of beauty.” Music is an artistic creation whose aim is to deliver beautiful knowledge and/or experience. Whether beauty is better understood by musical knowledge (the sounds themselves), musical experience (the process of listening to sounds) or both (most likely the case) is a discussion for another time. For now, let’s just say that music gets us closer to what we call “beauty.”

Musicians can come to better understand beauty by playing sounds. Listeners can better understand beauty by listening. As discussed before, music can tell a story, present an idea, or share an emotion. When there is meaning communicated through music it can be called program music. Programmatic music can be juxtaposed with absolute music, which is not explicitly about anything. Particularly during the Romantic era of western music, many composers focused on “art for art’s sake” by creating music with no subject matter and simply for the sake of beauty. A fantastic example (excuse my pun) can be found in Chopin’s “Fantasie Impromptu.”

Music for Its Own Sake

While the above purposes of music primarily involve extrinsic motivations, I believe the most potent and valuable reason for making music is intrinsic. Music, in all its forms, should be experienced for its own sake. Yes, we love music because it has utility, has benefits, and enhances other facets of our existence. Research has suggested that music has neurological, physical, emotional, spiritual and social benefits. But more importantly, music is good in-and-of itself. It’s elevating to recognize all the other purposes of music, but music’s primary purpose is to just be music. Although I mentioned absolute music in the previous section, it provides an example of music for its own sake. No justification is necessary to recognize that music is fantastic because that’s what it is. To answer the question posed above that asked “Why do music?” … just because.

Conclusion

Music does so many things. It can be used as an aural tool, it can communicate information, it can enrich our communities, it can provide entertainment, it can get humans in touch with beauty, and it can just be music. Sometimes a piece of music can do all of these things at once, and other times a piece of music can do one of those things extremely well. Hopefully this blog entry was able to stimulate some thought as to why music exists, but let’s not get too caught up with philosophical rumination on music’s purpose. Let’s end by taking a step back, let music “just be,” and be grateful that music exists.

I will close with a quote from one of my favorite philosophers, Friedrich Nietzsche:

“Without music, life would be a mistake.”

Sources

Foucault, M. (1965). Madness and Civilization. Random House, New York, NY.

Godt, I. (2005). Music: A practical definition. The Musical Times, 146(1890), 83-88.

Harmon, N. M., & Kravitz, L. (2007). The beat goes on: The effects of music on exercise. IDEA fitness Journal, 4(8), 72-77.

Mac Donald, R. (2005). Musical communication. Oxford University Press on Demand.

North, A. C., & Hargreaves, D. J. (1996). The effects of music on responses to a dining area. Journal of environmental psychology, 16(1), 55-64.

North, A. C., Hargreaves, D. J., & McKendrick, J. (1999). The influence of in-store music on wine selections. Journal of Applied psychology, 84(2), 271.

St. John, P. (2010). Crossing Scripts and Swapping Riffs: Preschoolers Make Musical Meaning. in Vygotsky and creativity: A cultural-historical approach to play, meaning making, and the arts (Vol. 5). Connery, M. C., John-Steiner, V., & Marjanovic-Shane, A. (Eds.). Peter Lang.

Titon, J. T. (1984). Worlds of music: An introduction to the music of the world’s peoples. New Yo

rk: Schirmer Books.