Written by Dr. Victor Ezquerra, instructor at Metro Music Makers

Introduction

Blues music was created by African-Americans in the United States in the late 1800s, and developed throughout the 1900s. It describes a style of music, a way of presenting musical ideas, different musical cultures that began in the United States and were developed internationally, and an emotion. Blues music tends to be about love and sadness, built off a simple I-IV-V 12-bar chord progression, contains very down-to-earth lyrics, and evolves with time. This blog takes a close look at the meaning, structure, and history of blues music.

And before we continue, consider Metro Music Makers if you are interested in piano lessons in Atlanta, vocal instruction, or another instrument. We work with kids through adults, and we bring music instruction to your home.

What is the blues?

The blues is several things: a feeling, a form of music, and a genre. The blues is considered an American roots music—one of the genres born and developed in the United States along with bluegrass, country, gospel, zydeco, traditional country, and Native American music. Those genres formed the “roots” for the tree of American music that would eventually bear fruits including rock, R&B, soul, and jazz. Here is a great article that situates American roots music in historical and cultural contexts. Below are several aspects, qualities, and interpretations that help explain and analyze the broad concept of blues music.

What is blues form?

The musical form (the way a piece of music is organized) of the blues tends to be relatively simple. Probably the most common form is the 12-Bar blues, which only uses three chords (I, IV, and V) and repeats after each twelve bars or measures. Although there are some slight variations to the chord progression (development and change of chords in a piece of music), the 12-bar blues chord progression is generally laid out as follows; each chord represents one bar/measure:

I I I I

IV IV I I

V IV I I

Lyrical form in the blues is also straightforward; it is usually AAB form. For each verse, a line of lyrics is sung every four bars. The “A” line is sung during the first four bars and repeated during the second four bars. The “B” line almost always rhymes with the A line and is sung during the last four bars. Below is an example of a blues verse in AAB form taken from B.B. King’s 1969 song, “The Thrill is Gone”—click here to listen to the song.

The thrill is gone, the thrill is gone away (A line, measures 1-4)

The thrill is gone baby, the thrill is gone away (A line, measures 5-8)

You know you done me wrong baby, and you’ll be sorry someday (B line, measures 9-12)

It is important to note that although the 12-bar chord progression and the AAB lyric form tend to be the most widely used, there are other forms of the blues.

What are the musical characteristics of the blues?

Because blues music evolved throughout the 20th century, its characteristics are dynamic and dependent on the specific type, phase, or sub-genre of the blues that is considered. However, several common characteristics can be identified.

Guitar and vocals are the instruments most frequently heard in blues music. Other instruments commonly heard are piano, harmonica, drums, and bass. Early on, not only were the lyrics of the blues improvised, but the instruments as well. Due to lack of accessibility and money, blues artists often had to make their own instruments. This would give rise to the one-stringed diddley bow, which was played with a bottle neck; the percussive washboard, which was played rhythmically with thimbles; an incredibly basic wind instrument (the jug); the spoons; and the washtub bass. Click the links to see and hear those resourceful and cool instruments!

Many of the characteristics found in the blues can be attributed to the influence of African music and culture. The use of improvisation, syncopation (emphasizing off-beat rhythms), social involvement (music during work/play), unique timbres (which can be raspy, twangy, and seem less “polished” than European music), call and response (one or more musicians plays/sings a musical phrase and another musician or group of musicians answer with a musical phrase), and blue notes (expressively bending/altering pitches in non-Western intervals)—these are all attributes that can be traced back to African influence.

What is blues music about?

As mentioned above the blues is a genre and a form, but it is also a feeling. You’ve probably heard the phrase “I’ve got the blues” or “I’m feeling blue.” Being “blue” refers to feeling sad, melancholy, downtrodden, heartbroken, down, guilt, despair, or other gloomy emotions. Although there are happy and uplifting blues songs, blues music is focused around harsh realities of life. Love is also a central subject—love and loss, being mistreated, and romance gone wrong are frequently sung about.

The presentation of the subject matter is expressive, honest, and straightforward. Since the blues is expressing pain, the performer(s) should have and understanding of and be able to communicate that pain. The language used in that communication is simple and down to earth. Lyrics are accessible and tend to avoid embellishment, convolution, picturesque descriptions, or grandiose settings.

When blues artists share their “truth,” both artists and audience feel that deep meaning. Not every blues artist has had a rough upbringing, struggled with poverty, had to do grueling labor, or had their heart broken the way they describe in their music. However, what (good) blues musicians are honest and truthful about is the feeling of having the blues. Genuine blues music isn’t learned—it’s felt.

Blues history

Blues music began in the southern United States in the late 19th century, most notably along the Mississippi delta. It was developed by African-Americans who blended European music with African music. The combination of those cultures and sub-cultures created what would become the blues. Early precursors that paved the way for blues music include work songs, field hollers, spirituals, folk ballads, and minstrels.

Early blues music (late 1800s – early/mid 1900s)

Delta blues is a term for early blues that refers to a specific geographic location, the Mississippi Delta. Typically, delta blues was performed with only one vocal part and one guitar (sometimes the piano); often the musician would perform alone by singing and playing at the same time. It was played in rural, informal settings—like a porch or a bar—and was not widely distributed through media. Lyrics were centered around things seen in the country—fields, trains, manual labor, etc. Out of the relatively few recordings that are still in existence from this time, many were done in the field by researchers like Alan Lomax instead of commercial recording companies.

Robert Johnson (1911-1938) is one of the most famous American artists of all time. He was a mysterious delta blues singer and guitar player who allegedly sold his soul to the devil at a crossroads in order to play guitar better. Very little is known about Johnson, who died in 1938 at age 27, so his music and persona have developed a legendary mysticism in American folklore. He is famous for songs like “Crossroads Blues” and “Love in Vain,” which would be covered by countless artists and eventually sell over half a million copies of his complete recordings despite the fact that he died in relative obscurity. Johnson also foresaw the transition of blues from the country to the city, as he sang about in “Sweet Home Chicago.”

During the same time, blues music existed in the northern U.S., albeit different from how it did in the south. The ensembles resembled early jazz instrumentation, the locations were in cities, and some artists experienced commercial success. Northern blues music contained characteristics derived from African music, but overall sounded much more refined and European when compared with delta blues. Mamie Smith’s (1891-1946) song, “Crazy Blues” (1920), has been credited as the “first significant vocal blues recording,” selling over 75,000 copies in Harlem alone over the course of a few weeks. W.C. Handy (1873-1958) wrote instrumental blues music, and was the first to publish a blues song in 1912—“Memphis Blues.” In 1914 he would publish “St. Louis Blues,” which became one of the most widely-known blues songs to come from the early blues era. Watch Handy perform that song on the Ed Sullivan show in 1949 . Out of these early types of blues music, the delta blues would be the one with a more lasting impact.

Urban blues music (around 1940 – around 1960)

The first major development of the blues came in the middle of the 20th century. Urban blues is the term used to describe blues during that time, which resulted from several changes. Firstly, blacks moved out of the southern United States to look for new opportunities during what was called the “Great Migration.” The “urban” designation points to a geographic change: blues music moved from rural areas to urban cities. Like “delta blues” refers to a specific location where the early blues occurred, Chicago blues is a term that refers to a major hub of the urban blues—Chicago. Secondly, by the mid-twentieth century, technology had changed the musical landscape. Electric instruments, vocal amplification, improved recording techniques, record players, and radio revolutionized the way people created and experienced all music, including the blues.

The urban blues introduced a new type of blues ensemble. Piano, harmonica, and especially drums and bass were frequently seen during performances instead of only a single voice with a guitar. The guitars that were being played were now electric instead of acoustic. Urban blues introduced slightly different subject matter (more city themes), less informal performances (actual concerts instead of casual “get togethers”), increased number of and better-quality recordings, and increased exposure to blues artists and music through several forms of media. This era of the blues would lay the foundation for the creation of other musical genres including rock, funk, soul, and R&B.

Following the evolution of the blues, Muddy Waters (1913-1983) was born in Mississippi and became a prominent blues musician in Chicago. With his modest guitar playing and unforgettable voice, Waters was an embodiment of the urban blues that would inspire countless other artists. Two of his more popular songs are “Got My Mojo Workin’” (1957) and “Hoochie Coochie Man” (1954). B.B. King (1925-2015), who was mentioned above, was another blues artist who followed the Great Migration from the south to the northern U.S., where he would be regarded as a legendary guitarist because of his unique and soulful solo guitar playing. His song, which was titled after the name he gave his guitars, “Lucille,” (1968) demonstrates his amazing solo playing and tells the story about how guitar “practically saved his life.”

Blues revival (1960s)

For roughly half a century, blues music had remained exclusively within black American culture. But by the 1960s, blacks in America had turned their attention to other genres such as R&B and soul music. The blues was no longer the most popular genre for black Americans. However, beginning in the 1960s, many white musicians in the U.S. and abroad had discovered the blues and began playing it. Although blacks still played the blues, its popularity amongst white audiences and musicians brought the genre to the foreground again, but in a different cultural context—hence—blues revival.

In the 1960s, blues music became faster and louder, venues and audiences got much larger, and it spilled outside of the U.S. into Europe. Rock mus

ic was built directly off blues music, with artists like Elvis and Chuck Berry drawing inspiration straight from blues form and content. Eric Clapton covered Robert Johnson’s “Crossroads” in 1966, and later released an album with B.B. King in 2000. The Rolling Stones derived their name from a Muddy Waters’ song, also covered Johnson’s “Love in Vain” in 1969, and worked frequently with the famous bluesman Howlin’ Wolf. Led Zeppelin, the Beatles, the Allman Brothers, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and many of their contemporaries recognized and harnessed the power of the blues. Innumerable musicians would continue to follow suit as time went on. There are many, many, many examples of how musicians from the 1960s onward have borrowed from, collaborated with, been inspired by, and learned from blues music.

Is blues music still around?

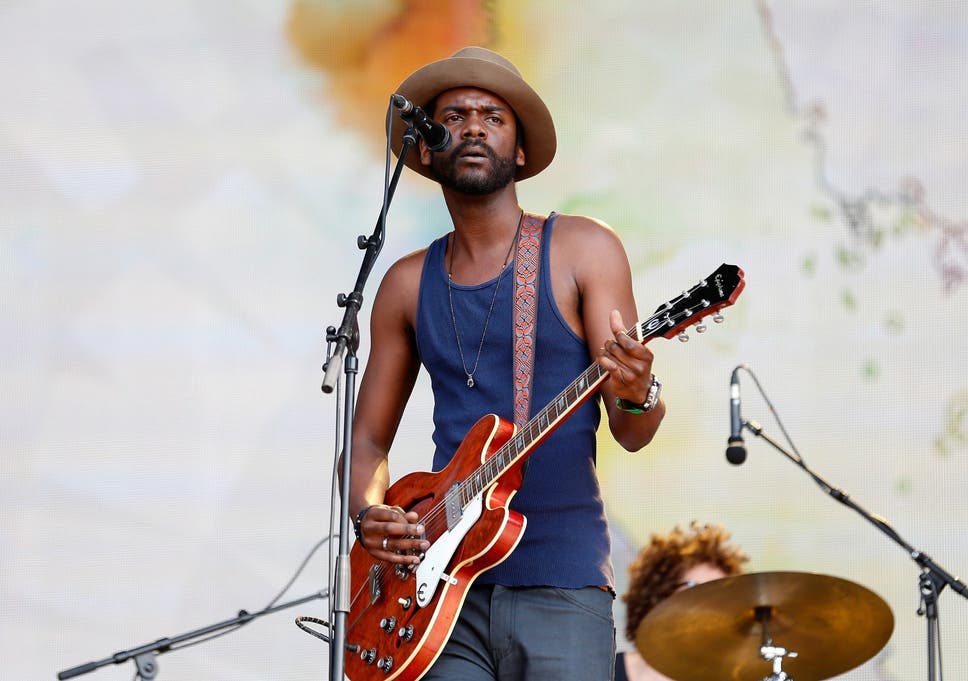

Yes, blues music still remains alive and well. A term that has been used to describe recent blues music is Americana. Although this term can be used to identify a contemporary version of any U.S. roots music (country, bluegrass, etc.), it also applies to blues. Americana highlights another phase in the evolution of roots music including the blues. The two artists pictured directly above are part of the newest generation of blues artists; Christone “Kingfish” Ingram on the left and Gary Clark Jr. on the right. Both artists continue the musical traditions of the past while advancing them into a present-day context. With careful listening, it is easy to notice the influence of the blues in music from all around the world today.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that the blues had humble beginnings and is relatively simple, it has sustained the interest of artists and audiences, spread around the globe, and adapted to changes imposed by time and place. The success of the blues stems from its adaptability, honesty, and universality. Whether it’s regarded as a feeling, genre, culture, form, and/or all of those things, the blues has been one of America’s most important contributions to the world.

If you’re interested in playing the blues, check out this 3-part video course I created for Metro Music Makers. If you need Alpharetta piano lessons or other in-home music instruction for your family, get in touch.

Citations:

1 Worlds of Music: An Introduction to the Music of the World’s Peoples. Shorter Version, 4th Edition. ISBN13: 978-1-337-10157-8. Editor: Titon. Authors: Cooley/Locke/Rasmussen/Reck/Scales/Schechter/Stock/Sutton

2 Jazz: The First 100 Years. Third Edition. ISBN-13: 978-1305637092. Martin, Henry and Waters, Keith.